Bill and Jennifer Browning live in the heart of one of the last, intact tallgrass prairies in the world: the Flint Hills in eastern Kansas. The waving green stems on their ranch are rich in nutrients and protein, supporting abundant wildlife and livestock.

“There’s nothing more beautiful to me than a prairie that is balanced, that blooms,” says Bill. “We want to see it passed from our hands in good or better condition than when we received it.”

Bill’s great-grandfather bought the first chunk of the Browning Ranch in 1907 for $4 per acre. He grew up working on the ranch and has lived on it for 50 years. The Browning family currently lease their grasslands for grazing cattle.

Encroaching trees threaten working lands and wildlife

Jennifer says that partnering with groups like USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has been “an amazing help” over the years, particularly for grazing management and weed control projects.

“The prairie is delicate and has to be nurtured,” she says. “It’s been a lifelong work and it’s paid off. We’ve seen recovery in many areas where the grass and the grounds have been repaired.”

Unfortunately, landowners across the Great Plains are facing an emerging threat to their working lands: trees like eastern redcedar are overtaking productive prairies. This tree invasion is one of the biggest threats to America’s grazing lands.

As trees spread and become denser, they reduce water supplies, decrease forage for livestock and wildlife, and cause hotter, harder-to-control wildfires.

“We are losing prairies to woody encroachment. If we can reverse that trend, we can keep this ecosystem intact, keep wildlife around, and keep the livestock industry in place,” says Luke Westerman, a district conservationist at the USDA Service Center in Greenwood County, Kansas.

Pioneering a new conservation approach

In 2021, the Brownings tried a new approach to eliminating unwanted woody species—the Kansas Great Plains Grassland Initiative (GPGI). Bill and Jennifer Browning were the first landowners to sign up for this recently launched initiative.

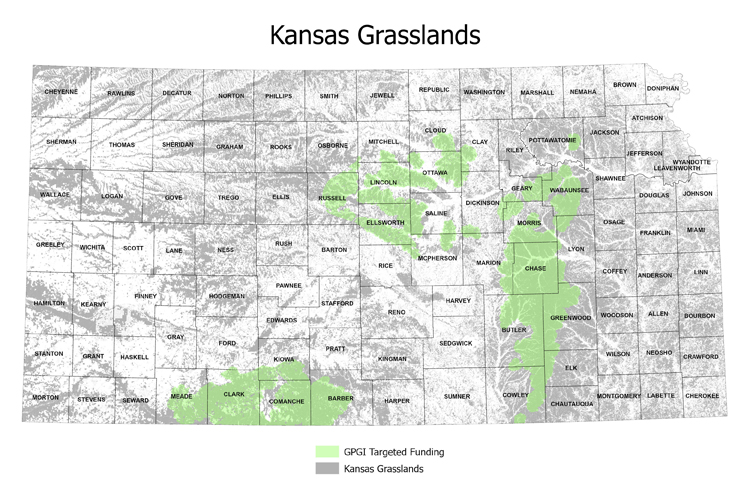

The GPGI is a rancher-driven, science-informed effort through NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife that helps landowners reduce vulnerability to woody plant encroachment in core grasslands. Kansas GPGI is targeting Environmental Quality Incentive Programs (EQIP) funds to financially fuel ranchers’ tree removal efforts in Flint Hills, Gypsum Hills, and Smoky Hills. This initiative is guided by NRCS’ framework for conservation action in the Great Plains biome, which aims to conserve America’s last remaining iconic grasslands. Similar GPGI efforts are launching in other Midwestern states.

See how NRCS helps ranchers with brush management (removing woody species from rangeland or grassland):

Westerman helped Bill inventory where trees had encroached in his pastures and to what degree. Westerman then developed a plan to help Bill reduce risk and vulnerability to these undesirable woody species on the ranch.

“If we can open Bill’s pastures up and get the young trees as well as the ones already producing seeds, then we can create a true tree-free and seed-free landscape,” explains Westerman. “That way, management down the road for his kids and grandkids will be much easier.”

Treatments include using a skid steer with a saw to cut down bigger trees, a pump-sprayer to spot-treat small seedlings and continued use of prescribed fire. The Brownings’ GPGI contract also includes cost-share for prevention as well as avoidance and monitoring to make sure more woody plants do not encroach on their land.

Leaving a legacy of healthy prairies

Thanks to Bill and Jennifer Browning’s passion for conserving the Flint Hills, the Browning Ranch is mostly free of invasive species, including weeds and trees.

“This program has sparked a renewed energy for us to go back out and do what needs to be done for the prairie,” says Bill.

Bill says he feels “loyalty to the critters that live in these grasslands,” including the plentiful prairie chickens that roam his pastures each spring. Prairie chickens, like other animals that rely on open grasslands, suffer when trees invade. Restoring the Flint Hills through GPGI gives these at-risk birds more places to nest and raise chicks.

Jennifer also enjoys seeing the native plants and animals on the ranch. She explains that part of their legacy has been teaching their daughter and grandchildren how to care for the prairie. “As our grandchildren learn about the prairie, it becomes a part of them, and that’s really a joy to see.”

Learn more about the Kansas Great Plains Grassland Initiative and about conservation practices that support both agricultural productivity and wildlife.

Brianna Randall is a freelance writer based in Missoula, Montana.